Sauropod DinosaursI study the anatomy, evolution, and paleobiology of Titanosauria, a globally-distributed group of sauropod dinosaurs.

|

Bone HistologyI employ bone histological data to interpret growth patterns in dinosaurs and other vertebrates.

|

Vertebrate Microfossil BonebedsI conduct field work in the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument in central Montana to investigate ancient ecosystems.

|

Sauropod Dinosaurs

|

Ever since the first discoveries of long-necked sauropod dinosaurs, they've awed, inspired, and confused us. For most of history sauropods were considered exemplars of extinction - too-big-for-their-own-good, small-brained, lumbering herbivores. Along with my colleagues from countries all over the world, my research has helped to dispel these myths. New discoveries and new kinds of data have repainted a picture of sauropods as dramatic dinosaurs that thrived throughout the entire Mesozoic Era. The secrets to their success lay in their remarkable paleobiology. After hatching from eggs no bigger than grapefruits, they grew as fast as living mammals, ate an entirely vegetarian diet, but were able to attain adult size when they were, at most, a few decades old. My current sauropod research is focused upon deciphering the anatomy, evolution, and paleobiology of two Late Cretaceous sauropod species from the Maevarano Formation of Madagascar: Rapetosaurus krausei and Vahiny depereti.

|

Bone Histology

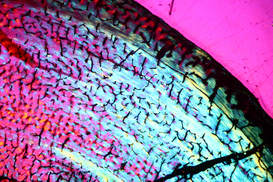

Cross section of the tibia from Majungasaurus, a theropod dinosaur from Madagascar.

Cross section of the tibia from Majungasaurus, a theropod dinosaur from Madagascar.

One of the craziest things about dinosaurs is how diverse their body sizes are. The giant sauropods weighed more than 20 million times as much as the tiniest dinosaurs (like the modern hummingbird)! A large component of my research program is focused on dissecting the differences in the growth strategies of dinosaurs and their living relatives. In order to garner data to help address these questions, my colleauges and I study the microscopic structure of bones. Though most dinosaurs have been extinct for more than 65 million years, their bones preserve patterns of bone mineral, density and architecture of blood vessels and cells, and the history of remodeling. These features are directly comparable to the same features in living animals, and we use them as a proxy for determining growth rates in fossil organisms. We've learned that dinosaurs all grew at rates more similar to those of living birds and mammals than to reptiles, but that not all dinosaurs grew exactly the same way. Recently, my students and I have been working with modern animal skeletons to test some of our hypotheses about how the signals of growth are conserved across time and environments deep within bones.

Vertebrate Microfossil Bonebeds

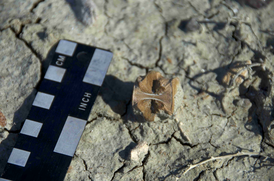

Locating the F. V. Hayden dinosaur site in the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, Montana.

Locating the F. V. Hayden dinosaur site in the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, Montana.

Vertebrate microfossil bonebeds are accumulations of the resilient hard body parts of ancient organisms. These tiny teeth, scales, and vertebrae may seem insignificant, but they provide the ecology of ancient ecosystems in great detail. Along with Ray Rogers (Macalester Geology), the Bureau of Land Management, and a number of talented undergraduate students, we're investigating microfossil bonebeds within the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation exposed in gorgeous Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument (UMRBNM). Our work includes field work aimed at discovering new bonebeds, lab-based work directed at decoding aspects of taphonomy, taxonomy, and diversity in these ancient ecosystems, and some library and field-based sleuthing that targets the identification of localities within the UMRBNM discovered by some historic figures in paleontology, like Ferdinand V. Hayden (who discovered the first body fossils of dinosaurs in North America in the UMRBNM) and Edward D. Cope (who discovered the enigmatic horned dinosaur Monoclonius in the UMRBNM).